Go to any informal settlement in Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka, or to the outskirts of a city along its coast, such as Khulna, and it doesn’t take long to find communities that have relocated or been displaced. Their homes may have been destroyed —often repeatedly—by a sudden onset natural hazard such as a cyclone; or their livelihoods may have been degraded by slow-onset effects of climate change, such as the salinization of soil and water sources. Sometimes it is a combination of both.

The reason for this ‘distress migration’ is never singular and rarely straightforward. It lies in a confluence of extreme weather and hazards, climate change, and public policy. As climate change accelerates and weather variability grows, life in hazard-exposed areas will become progressively harder. States have two policy alternatives to in situ misery or distress migration: in situ adaptation, helping people remain where they are, or planned relocation from danger, where this is not possible.

Climate-motivated planned relocation projects are currently infrequent, but will become much more commonplace. As governments increase their work on planned relocation, they will turn to existing providers and sources of development finance. Currently, multilateral development banks (MDBs) are not well positioned to respond to this emerging demand: there is no internationally agreed framework or set of principles on planned relocation. Nor are countries well positioned to make the case for support: many lack a well-developed domestic policy structure.

It is important that this changes. In the paper we published today, we examine emerging public policy on planned relocation, draw from existing standards on development-forced displacement and resettlement, and explore entry points for development finance. We also build the case for MDBs to support countries in planning, implementing, and financing planned relocation in the context of climate change.

Emerging public policy on planned relocation

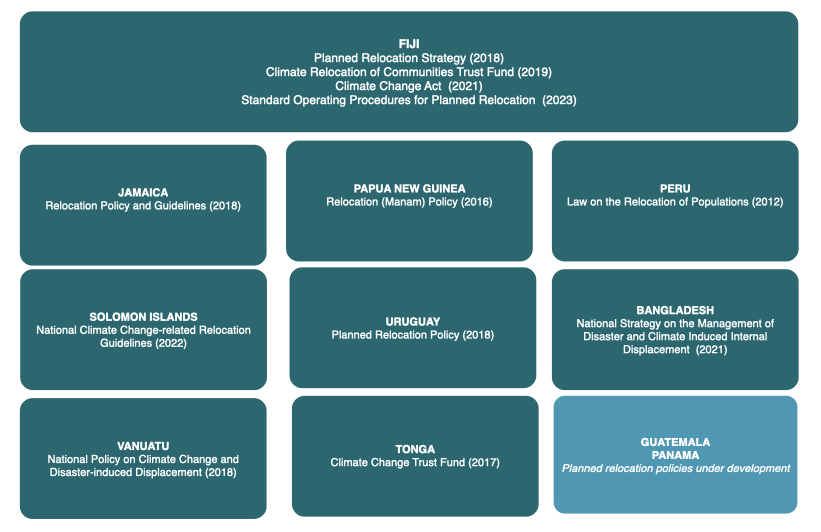

Public policy on planned relocation is being driven by a group of first movers (figure 1), all on the frontlines of climate change and already facing high disaster risks. While these frameworks set out a government’s approach, and signal to partners that it’s a priority issue, the instruments often lack key elements, especially concerning financing.

Fiji has one of the best-developed and most comprehensive strategies: it provides a legal framework, a clear policy approach, defines roles and responsibilities across duty bearers, affected communities, and stakeholders, as well as a vehicle to mobilize domestic resources, in addition to channeling external finance. Many countries are much further behind.

Figure 1: First movers – countries with public policy on planned relocation

A much larger number of countries have identified planned relocation as an area of policy importance in their National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), but without necessarily taking comprehensive steps. A 2023 study of 49 NAPs submitted to the UNFCCC found that less than half—24—included references to planned relocation, and that only 19 included concrete commitments related to planned relocation (figure 2).

Figure 2: Do National Adaptation Plans mention planned relocation?

Map created using Datawrapper; national borders set by Datawrapper.

Integrating planned relocation into national policies matters. Countries will increasingly need to shift from ad hoc planned relocations to an approach that is systematic, rights-based, and able to attract non-grant MDB funding. Given the diversity of contexts, country approaches will need to incorporate flexibility while also providing clarity and predictability.

The case for MDB engagement

Planned relocations are complex and costly. Governments will need assistance in preparing for them, implementing them, and funding them. MDBs can offer their resources in three principal areas: (i) technical assistance, (ii) safeguards, and (iii) finance.

Technical assistance

Most countries are not currently ready to undertake planned relocations or to seek external finance—and especially non-grant finance—for planned relocation projects. To support bankability, countries seeking development finance from MDBs are likely to require technical assistance given the complexity and the relatively underdeveloped state of planning in many countries. MDBs can assist or support:

- In establishing sound governance procedures for planned relocation, following clear decision protocols developed following consultations. MDBs can support countries in building capacities in data-gathering and analysis, through funding for technical agencies or discrete projects and direct technical support.

- In improving data availability. The data needed will vary based on context and the indicators chosen to inform decision-making parameters. MDBs can support countries in building capacities in data-gathering and analysis, through funding for technical agencies or discrete projects and direct technical support.

- The coordination of planned relocation projects, both in policy planning—ensuring relocation is considered in adaptation discussions—and during project planning and implementation. This is critical given the potential for high levels of friction between different actors in crosscutting policy spaces. This may involve close collaboration with national development banks; the creation of a trust fund or similar national-level coordinating funding instrument; and the development of clear governance frameworks to reduce frictions over funding sources and commitments. MDBs have previous experience in supporting such engagements in Tonga and Bangladesh.

- In preparing and undertaking cost-benefit analyses. Cost-benefit analyses prior to planned relocation projects are currently rare: this presents financial governance risks and makes it challenging to obtain non-grant support. MDBs have widespread and deep experience in conducting cost-benefit analyses, and are well-placed to offer countries advice and direct support in ex-ante assessments for planned relocation projects.

- Support countries and subnational actors in preparing project proposals. Many governance actors responsible for planned relocation projects are likely to have limited administrative capacity or experience in seeking international funding. MDBs can build on existing efforts, such as the World Bank’s Gap Fund, to create a pipeline of projects eligible for financing.

- The implementation of planned relocation projects, building on existing experience to ensure that projects are consultative, equitable, and efficient.

- Countries in evaluating planned relocation projects. Few evaluations have so far been undertaken, and there remain questions as to how projects should most effectively be implemented and how and when they should be assessed.

Safeguards

Planned relocation projects uproot communities’ lives. They will be increasingly necessary, but come with immense risks. It is crucial that any approach to planned relocation is undertaken with appropriate safeguards, delivered through consultation to ensure equitable outcomes.

MDBs are well placed to develop a framework for equitable and consultative planned relocation projects. In the absence of sufficient national safeguards, existing MDB safeguarding can provide a foundation for planning and implementation, especially if drawing on lessons from the many development-forced displacement and resettlement projects already undertaken. The World Bank’s 2018 environmental and social framework, consisting of 10 environmental and social standards (ESSs), includes standards on land acquisition, restrictions on land use, and involuntary resettlement (ESS5).

The objectives of ESS5 are to:

- To avoid involuntary resettlement or, when unavoidable, minimize involuntary resettlement by exploring project design alternatives.

- To avoid forced eviction.

- To mitigate unavoidable adverse social and economic impacts from land acquisition or restrictions on land use by: (a) providing timely compensation for loss of assets at replacement cost, and (b) assisting displaced persons in their efforts to improve, or at least restore, their livelihoods and living standards, in real terms, to pre-displacement levels or to levels prevailing prior to the beginning of project implementation, whichever is higher.

- To improve living conditions of poor or vulnerable persons who are physically displaced, through provision of adequate housing, access to services and facilities, and security of tenure.

- To conceive and execute resettlement activities as sustainable development programs, providing sufficient investment resources to enable displaced persons to benefit directly from the project, as the nature of the project may warrant.

- To ensure that resettlement activities are planned and implemented with appropriate disclosure of information, meaningful consultation, and the informed participation of those affected.

Adapting this approach to planned relocation projects in the context of climate change, and building in guidance produced by non-governmental entities, MDBs should develop a set of standards on planned relocation in the context of climate change. This would lay the foundations for MDBs and others to then build an operational and compliance framework to guide investments, while also providing certainty to borrowers on loan conditionality.

Financing

Once the demand for finance and a policy framework to respond to the challenges of planned relocation are set out, countries can draw on their allocations from MDBs. While in theory this is straightforward, the capital intensive, complex, and protracted nature of planned relocation can present operational challenges.

Climate finance has a role to play: planned relocation is a response to a negative externality, and governments should receive support. While planned relocation is not yet included in the strategic documents of the global climate funds, there are entry points where it can be presented as part of efforts to adapt to climate change. On the demand side, countries can create an enabling environment for adaptation finance by putting in place clear and reliable policies and guidelines, and aligning their vehicles(such as trust funds) with the fiduciary standards and social and environmental safeguards of the global climate funds. On the supply side, MDBs can offer proven approaches to co-finance with global climate funds, and others, to scale investments and to crowd in concessional resources, promote efficiencies, and strengthen coordination.

MDBs should also prepare to offer loans supporting planned relocations, preferably at concessional rates over long repayment schedules. For this to be feasible, careful cost-benefit analyses will be necessary.

How to re-position MDBs

In preparation of the expected demand from MDB clients for finance and technical assistance to implement policy and programs on planned relocations at-scale, the following five recommendations are made to re-position MDBs:

- On technical assistance, starting from a set of general principles, a common approach should be developed to cover terminology, due diligence, engagement and consultation requirements, identify methods and tools to assess and manage potential risks, set broad conditions under which MDBs are prepared to provide support to a project, as well as monitoring and performance indicators, disclosure standards, and grievance and accountability mechanisms.

- MDBs should increase efforts to build and disseminate an evidence base on what works and what doesn’t in planned relocation as its relevance to communities grows. Capturing, analyzing, and disseminating the growing body of knowledge, practice, and evidence requires coordinated efforts. The Santiago Network, established under the UNFCCC, may offer a vehicle for this if better resourced.

- MDBs should also prepare to provide direct technical assistance in a range of areas. These include in developing protocols; gathering and managing data; improving governance structures; undertaking cost-benefit analysis; implementing projects; and evaluating relocations.

- On safeguards, drawing on MDB involuntary resettlement frameworks, develop a common approach to provide a set of building blocks while still facilitating context-specific and differentiated implementation approaches.

- On finance, MDBs should explore how existing modalities can be applied and where innovative financing arrangements, including co-finance, can be deployed to increase investments in planned relocation, where adaptation limits have been reached.

Global climate funds need to consider how they can better respond to the demand for finance and technical assistance. This will require a shift from the current passive and theoretical position of funding planned relocation to one that actively supports investment. This starts with revisiting strategic documents to explicitly recognize planned relocation.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.