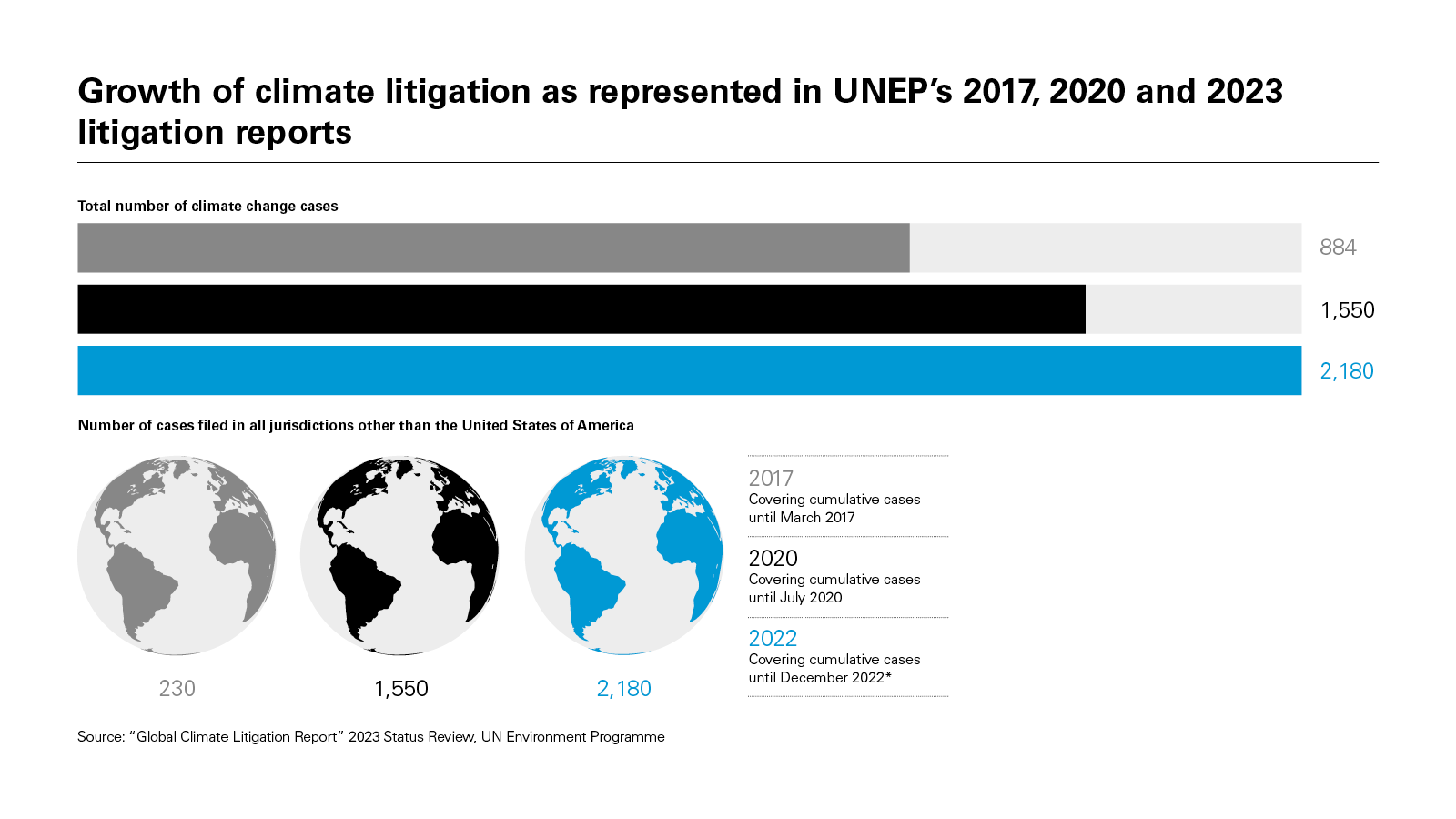

Over the past decade, climate change disputes numbers have been consistently rising. But this phenomenon has only marginally affected Africa so far, as most disputes have been located in North America, Europe and Australia. This is a paradox, given the impact climate change has and will have on the African continent. And indeed, African states are paving the way to implement measures to combat the adverse effects of climate change. Such endeavors may collide with the continent’s aspirations for economic growth. The resulting conflicts, in turn, may trigger disputes both before local courts and international arbitral tribunals.

African states are paving the way to combat the adverse effects of climate change

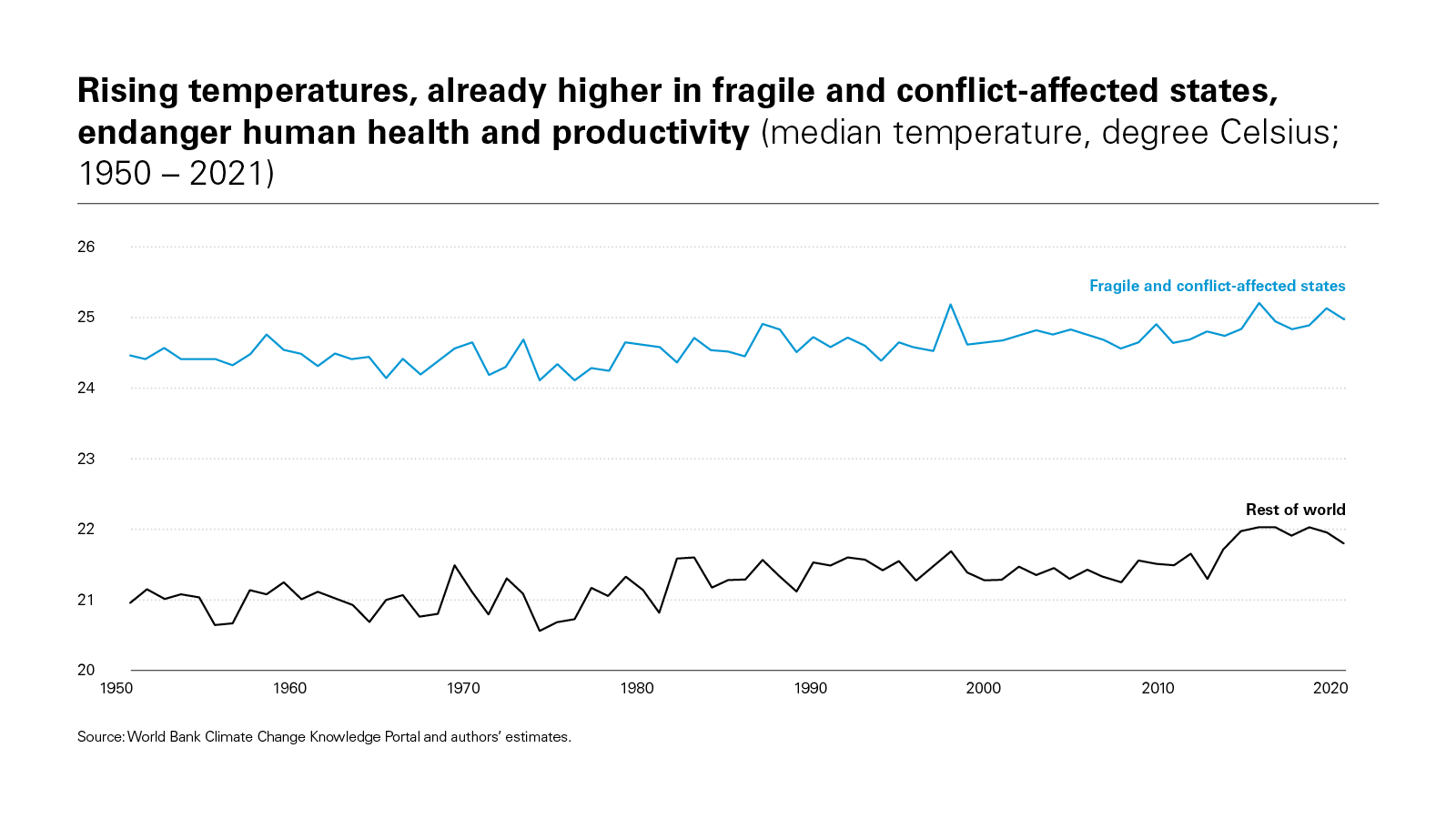

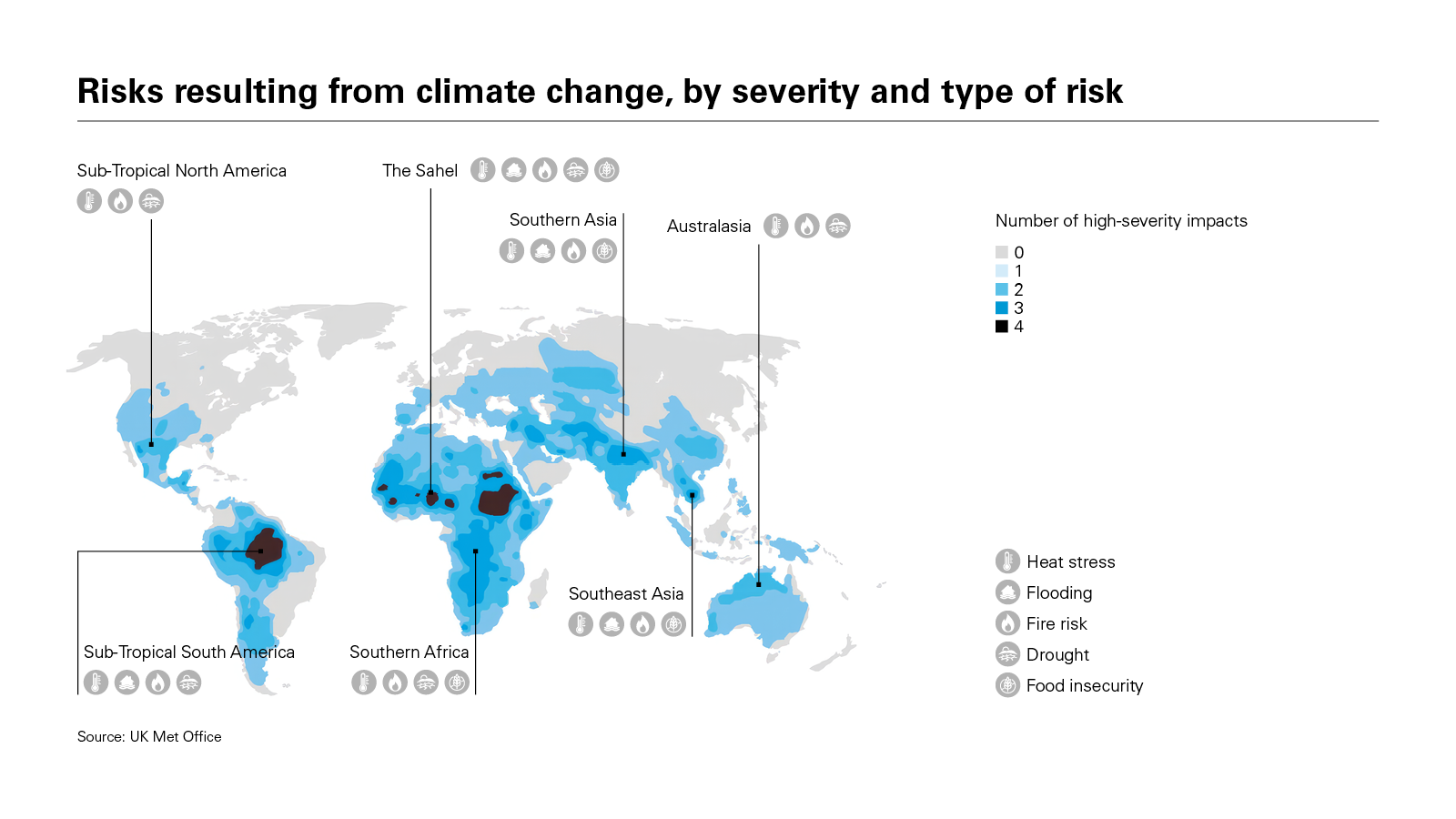

A perfect template for climate change disputes

Climate change poses significant challenges to Africa. According to the World Meteorological Organization, the average rate of warming in Africa was +0.3 °C/decade during the 1991 – 2022 period, compared to +0.2 °C/decade between 1961 and 1990. This is slightly above the global average. The warming has been most rapid in North Africa, which was gripped by extreme heat, e.g., fueling wildfires in Algeria and Tunisia in 2022. Climate change not only leads to increased temperatures, but also to changing rainfall patterns and more frequent extreme weather events. All these phenomena impact agriculture, water resources and biodiversity. Climate change can also exacerbate the spread of diseases such as malaria and impact public health infrastructure. Similarly, changes in temperature can affect energy demand and the availability of hydropower resources, which many African countries rely on. Finally, extreme weather events can damage roads, bridges and buildings, affecting transportation and economic development.

Sub-Saharan African countries are especially vulnerable because of limited resources for adaptation and a high dependence on climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture, hydropower energy and tourism.

As a result, efforts to address climate change in Africa involve adaptation strategies, renewable energy development and international cooperation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Accordingly, African heads of state and government gathered for the inaugural Africa Climate Summit (ACS) in Nairobi, Kenya, from September 4 to 6, 2023, and released a declaration by which they called for, among other things:

US$2.8 trillion

Implementing Africa’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) will require up to US$2.8 trillion between 2020 and 2030

- An increase in Africa’s renewable generation capacity from 56 gigawatts (GWs) in 2022 to at least 300 GWs by 2030

- A shift in exports of energy-intensive primary processing of Africa’s raw material back to the continent

- Access to, and transfer of, environmentally sound technologies, including technologies to support Africa’s green industrialization and transition

- Design of global and regional trade mechanisms that enable products from Africa to compete on fair and equitable terms

- A request that trade-related environmental tariffs and non-tariff barriers must be subject to multilateral discussions and agreements and not be unilateral, arbitrary or discriminatory measures

- Acceleration of efforts to decarbonize the transport, industrial and electricity sectors through smart, digital and highly efficient technologies such as green hydrogen, synthetic fuels and battery storage.

- Design of industry policies that encourage global investment to locations that offer the most and substantial climate benefits, while ensuring benefits for local communities

- Implementation of a mix of measures that elevate Africa’s share of carbon markets

Whether actually adopted or not, these measures may trigger climate change disputes: On the one hand, if the subscribing African states fail to adopt and implement these measures effectively, individuals or interest groups may sue these states to force them to act. On the other, if adopted, these measures may contrast with these states’ attempts to grow their economies. Many African nations rely on the exploitation of their fossil fuel resources to boost their economies and create a middle class. In addition, climate-resilient agricultural practices often require changes that disrupt traditional methods, affecting livelihoods in the short term. At the same time, strict environmental regulations and emission reduction targets can limit industrial expansions and foreign investments. This conflict of goals is the perfect template for many climate change-related disputes.

What types of disputes may unwind?

Considering the conflicting interests of the various stakeholders (states, populations, investors), climate change disputes in Africa can arise, have arisen, and will arise in various ways. That said, so far, only 15 climate change disputes related to Africa have been registered by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, Columbia Law School, Columbia University in the City of New York, which tracks climate change disputes worldwide.

Three categories of climate change-related disputes involving Africa are most likely to arise: liability and compensation disputes; environmental regulations disputes; and investment disputes.

Liability and compensation: In some cases, individuals, communities, or even states and municipalities may seek compensation for losses and damages caused by the effects of climate change. This can lead to legal actions against entities, such as fossil fuel companies, alleging responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions and their contribution to climate change. A good example is the case of Okpabi et al. v. Royal Dutch Shell et al. In this case, 42,500 Nigerian citizens sued Royal Dutch Shell, seeking to hold the parent company responsible for the alleged environmental damage and human rights abuses by its Nigerian subsidiary, Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Ltd (SPDC), perpetrated in the Niger Delta. The claimants alleged that oil spills and pollution from pipelines operated by SPDC caused substantial environmental damage, so that natural water sources cannot safely be used for drinking, fishing, agricultural, washing or recreational purposes. What is remarkable, however, is that this dispute was not brought before Nigerian courts, but before English courts (based on Royal Dutch Shell’s seat). The decision on the merits is still pending before the UK Supreme Court, after it had been dismissed in the first instance. With the growth of African economies, it is likely that such disputes will also occur more in Africa. That said, for enforceability purposes, they may still be brought to the seats of the sued companies.

Environmental regulations: Legal disputes may arise over the implementation and enforcement of environmental regulations aimed at mitigating climate change. Industries and local governments may challenge the legality of such regulations, leading to court cases or investment arbitrations, depending on the stakeholders involved. For instance, in West Virginia et al. v. EPA, 20 states and several energy companies had sued the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for overstepping its powers. The case revolved around the Clean Power Plan (CPP) proposed by the EPA in 2015. It aimed to regulate emissions at existing power plants by using technology and shifting to clean energy sources. The CPP faced challenges, leading to court stays and was never enforced. The Trump administration introduced a similar Affordable Clean Power rule in 2019, which also faced legal challenges. Even with the change in administration to President Biden in 2020, the case remained relevant, because the EPA kept its intentions to include certain emissions controls, so that the central issues of the case—the EPA’s regulatory authority—still applied. On June 30, 2022, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the EPA lacked the authority to regulate emissions from existing power plants based on generation shifting mechanisms, thus invalidating the Clean Power Plan. Even so, the EPA can still regulate emissions at existing plants using emissions reduction technologies.

If such a dispute about overstepping powers by introducing new environmental regulation involves a foreign investor, it may end up in a dispute before an investment arbitration tribunal.

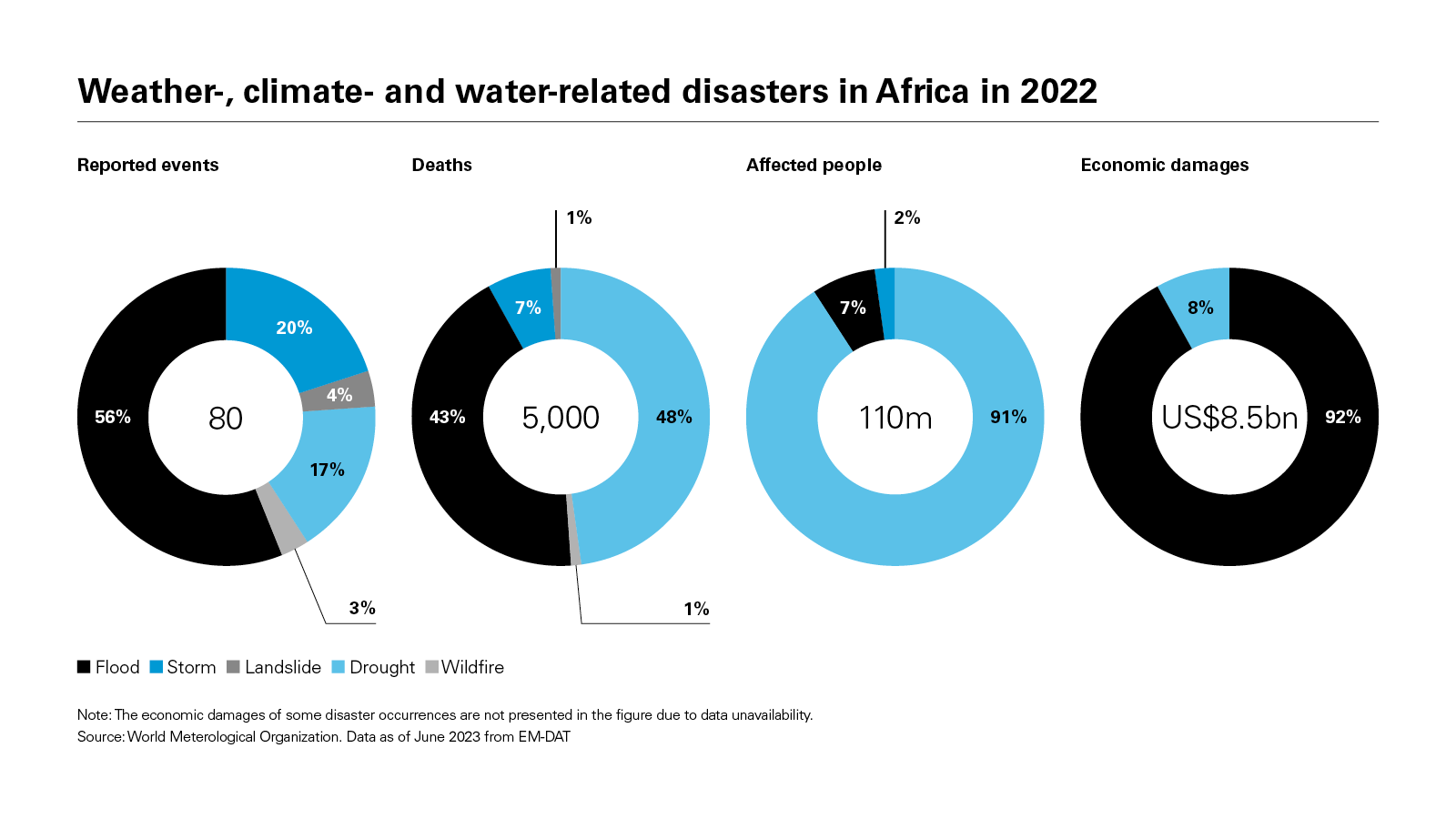

US$8.5 billion

Weather, climate and water-related hazards in Africa in 2022 caused more than US$8.5 billion in economic damages

But disputes over environmental regulations can also arise when individuals or NGOs request their governments to act: A good example is Africa Climate Alliance et. al. v. South African Minister of Mineral Resources & Energy et. al. The applicants allege that the procurement of 1,500 MWs of new coal-fired power allowed by the Ministry represents a severe threat to the constitutional rights of the people of South Africa, especially their environmental rights, the best interests of the child, and the rights to life, dignity and equality, among others. On November 17, 2022, the High Court of South Africa held a hearing on the matter of the respondents’ document production. The Court delivered its interlocutory judgment on December 9, 2022, which ordered that the minister must release records relating to the decision to include new coal power in the 2019 Integrated Resource Plan for Electricity (IRP), and to the 2020 ministerial determination for new coal issued under the IRP. Should the minister fail to release the records, the applicants will be entitled to proceed with the case against the minister without his opposition. It is unknown whether the ministry complied with these orders.

Investment disputes: As anticipated above, investment arbitration disputes related to climate change involving African countries have not occurred so far, but are very likely to be launched. In fact, investment disputes often revolve around issues such as environmental regulations, changes in government policies affecting investments and the effects of climate change on specific industries. A prominent example is Rockhopper v. Italy: In 2015, the Italian government re-introduced a ban on oil & gas exploration within 12 miles of the Italian coastline that it had lifted in 2012. In 2017, UK company Rockhopper Exploration Plc, along with its Italian subsidiary, filed a claim for compensation alleging violations of the investor protection provisions of the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). The claim concerned its interests in the Ombrina Mare oil rig, for which it was hoping to obtain a production concession from the Italian government before the introduction of the ban. On August 23, 2022, the ICSID arbitral tribunal ordered the Italian government to pay €184 million to the claimants.

Similar scenarios are very likely to appear in Africa. For instance, if an African government decides to introduce stricter environmental regulations to address climate change, foreign investors in industries like mining, energy or agriculture may challenge these regulations through investment arbitration. They might argue that the new rules harm their investments or violate international treaties. But the risk of disputes does not only come from the fossil fuel industry: As Africa invests in renewable energy projects to mitigate climate change, disputes can arise between governments and foreign investors regarding contracts, incentives and policy changes related to these projects. A prominent example are the many investment cases of investors against Spain (and to a lesser extent, Italy) for withdrawing state incentives for the solar industry. Similarly, climate-resilient infrastructure projects can involve significant foreign investments. Disputes may emerge over contract issues or government decisions related to these projects. Finally, climate change can exacerbate land and resource disputes in Africa, leading to conflicts between indigenous communities, governments and foreign investors.

Investment arbitration concerning climate change in Africa underscores the intricate relationship between environmental sustainability and economic development. Notably, African states have taken proactive measures to mitigate the potential risks associated with such disputes. For instance, the 2012 Model Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) placed obligations on both states and investors, with the explicit aim of achieving a balanced distribution of rights and responsibilities among the signatory parties. In doing so, the SADC model BIT even preceded the much-acclaimed 2019 Dutch model BIT. The SADC model BIT comprises numerous provisions that oblige investors to adhere to commitments pertaining to environmental preservation, human rights and anti-corruption measures.

Additionally, a commonly observed environmental provision is the general exception clause, which safeguards a state’s sovereign right to enact and apply legislation for environmental protection, ensuring that the BIT does not restrict this authority. Furthermore, non-derogation clauses, often included in BITs concluded by Nigeria and Tanzania, specifically articulate that international investment agreements should not be interpreted as permitting any deviation from or waiver of compliance with established environmental standards.

In the same vein, several African states have incorporated exceptions or elucidations within their international investment agreements (IIAs) to address substantive legal protections, including the fair and equitable treatment (FET) standard, indirect expropriation and the national treatment standard. These provisions explicitly declare that environmental measures should not be considered as unfavorable treatment contravening the FET standard, thus empowering states to enact environmental regulations without the fear of arbitration. Morocco, for instance, has included such an exclusion related to FET in several of its IIAs. As an illustration, the Morocco-Japan BIT of 2020 specifies that “[m]easures of a Contracting Party that are designed and applied to protect legitimate public welfare objectives, such as public health, safety and the environment, do not constitute indirect expropriation.” Older Moroccan BITs, such as the one with Germany (1961) or France (1996), do not contain similar provisions.

Strategies for navigating the climate litigation landscape in Africa

The ongoing impact of climate change and the attempts of African states, but also of African communities, to combat its negative effects will no doubt contrast with conflicting economic interests. This will trigger disputes on all possible avenues: It may lead to disputes before state courts (perhaps with an increase of involvement of African domestic courts) but also to large-scale investment disputes before investment arbitral tribunals. All involved actors (states, local communities, as well as domestic and foreign investors) should be prepared to address the issues resulting from the need to combat climate change and (if possible) prevent time and cost-consuming disputes. For example, governments should consider the effect of new legislation on current domestic and foreign investments, and contemplate strategies to negotiate and settle potential disputes at the outset. At the same time, investors should consider carefully the environmental and emissions impact of their investment and the likelihood of changes in legislation, perhaps by looking into legislative trends in the region or in similar jurisdictions. Both governments and corporates/investors should also aim at involving affected local communities and NGOs in discussions on how to handle the issues a project or a change in regulation/legislation may pose.

If disputes cannot be avoided, the stakeholders need to factor in the unpredictability of the outcome of such disputes, ones that are still new to the legal world.

In any event, all stakeholders are well advised to seek the support from experienced counsel with cross-border experience in climate change-related disputes. Such legal advice can help anticipate potential disputes, risks and pursuit of their rights based on similar experiences in other jurisdictions. This is particularly true for virtually all African jurisdictions. Despite an enormous potential for climate change-related disputes, for lack of their own decisions, they will need to look at decisions adopted in North America, Europe and Australia for guidance.

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

View full image: Growth of climate litigation as represented in UNEP’s 2017, 2020 and 2023 litigation reports (PDF)

View full image: Growth of climate litigation as represented in UNEP’s 2017, 2020 and 2023 litigation reports (PDF) View full image: Weather-, climate- and water-related disasters in Africa in 2022 (PDF)

View full image: Weather-, climate- and water-related disasters in Africa in 2022 (PDF) View full image: Rising temperatures, already higher in fragile and conflict-affected states, endanger human health and productivity

View full image: Rising temperatures, already higher in fragile and conflict-affected states, endanger human health and productivity View full image: Risks resulting from climate change, by severity and type of risk (PDF)

View full image: Risks resulting from climate change, by severity and type of risk (PDF)