Good news tends to be scarce in the international conservation arena, so the recent confirmation of the presence of a wild cheetah in Djibouti after an absence of more than 30 years from this Horn of Africa country had wildlife researchers smiling broadly.

But one cheetah doesn’t necessarily make a population, they warned.

Cheetahs are one of the three species that make up the continent’s iconic “big cat” triumvirate. And, like their lion and leopard counterparts, cheetah numbers have been plummeting and their current geographical range has shrunk dramatically.

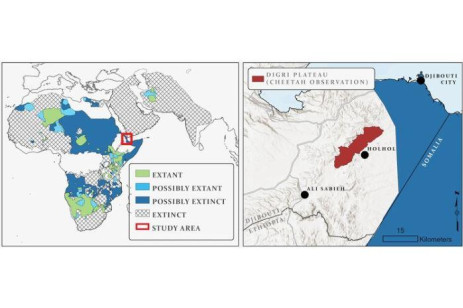

Formerly widespread through much of Africa and south-western Asia, cheetahs are now found in only about 9% of their historical range. Researchers suggest that this recent rapid contraction and other factors, such as their low genetic variability, warrants a change in conservation status – on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List – from “vulnerable” to “endangered”.

Like other top order predators, cheetahs occur at low densities and require huge home ranges, anywhere between several hundred to more than 3,000 square kilometres, so they are particularly vulnerable to habitat loss and fragmentation resulting in small, physically isolated populations.

Cheetah conservation has become acute in East Africa. Research has shown that only around 300 cheetahs remain in this whole region. Illegal trafficking for the pet trade is a particular problem. In Ethiopia and Somalia, two countries neighbouring Djibouti, the poaching of cheetah cubs for smuggling into the Arabian Peninsula is a major concern.

biodiversity survey in Djibouti, in the rugged and remote Digri Plateau. Picture: Evan Buechley, accessed through GroundUp” />

biodiversity survey in Djibouti, in the rugged and remote Digri Plateau. Picture: Evan Buechley, accessed through GroundUp” />Researcher Dr Mark Chynoweth, who headed the search for mammals during a biodiversity survey in Djibouti, in the rugged and remote Digri Plateau. Picture: Evan Buechley, accessed through GroundUp

In 2021, the World Bank contracted American ornithologist and vulture expert Dr Evan Buechley to undertake a biodiversity survey in Djibouti ahead of a development project. A University of Utah postgraduate researcher, then on the staff of US-based conservation group HawkWatch International, he assembled a team of eight, later led by his HawkWatch colleague, Dr Megan Murgatroyd.

Cape Town-based Murgatroyd is also a research associate at the FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology at the University of Cape Town, and started her research career studying Verreaux’s eagles in the Cederberg region.

She explained that their Djibouti objective was to do a broad-scale biodiversity study across the country, looking at mammals, birds and plants. “It was very exploratory because so little work has been done there,” she said.

Buechley said the team’s work had been “really the first large biodiversity assessment ever done in Djibouti”.

“There have been site-specific or species-specific studies, but we were doing a biodiversity assessment in a transect that ran across the entire country. We didn’t know what to expect,” he was quoted saying in a recent research article for the University of Utah, Are cheetahs making a comeback in East Africa?

The mammal team used camera traps to record the presence of large mammals during two trapping surveys: 48 camera traps for 42 days during the autumn of 2021, and then 41 cameras during the spring of 2022 over 25 days.

While recording a cheetah was always an outside possibility, it really wasn’t expected.

Location maps showing Djibouti and the remote Digri Plateau where the cheetah was photographed. Illustration: Hawkwatch International

Houssein Rayaleh, a member of the research team representing Association Djibouti Nature and the Djibouti Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, explained that although cheetahs were presumed to possibly still exist in the country, there had been no confirmed sightings in Djibouti for more than 30 years.

The cameras were set at carefully selected sites to shoot bursts of three frames when triggered by a passing animal. Although 27 of the cameras malfunctioned or were broken or stolen, the team was able to process images from more than 1,300 trap nights in total.

The camera traps picked up caracal, spotted hyena, and three potential cheetah prey species: dorcas gazelle (a small, common antelope), gerenuk (a long-necked medium-size antelope also known as the giraffe gazelle), and Salt’s dik-dik (another small antelope).

Then came the exciting find. At 1:59am on 30 March last year, a camera on the rugged and remote Digri Plateau in the south-east of the country recorded six images of a cheetah of unknown gender.

Murgatroyd cautioned that further research was necessary to assess the possibility of cheetah population(s) in Djibouti.

“This could simply be a vagrant individual, or it could indicate that there is an important remnant cheetah population in the country,” she said. “Given the country’s rapid development and high biodiversity, we hope further research will be conducted to assess whether this is indeed an important habitat for this quickly declining species.”

Buechley was also wary of drawing hard conclusions.

“They’re [cheetahs] not doing good – they’re diminishing, their range is contracting, and you see an individual well outside, well north, of its known range,” he said.

“That said, cheetahs roam very widely. This could just be a lone individual that was on 1,000-kilometre trek across the Horn of Africa, never to be seen in Djibouti again. So there’s that.”

A cheetah in full flight in the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park. Picture: John Yeld, accessed through GroundUp

But the mammal team led by Dr Mark Chynoweth, also of Utah State University, had found the Digri Plateau area to have the highest mammalian species richness in the study area. “This may indicate that there is sufficient prey available to support a cheetah population,” Chynoweth suggested.

The researchers formally announced their remarkable find in this year’s spring edition of CAT News, a publication of the Cat Specialist Group which is a component of the Species Survival Commission of the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

And it wasn’t only the cheetah that had caught the researchers’ attention.

“The bird life was pretty fantastic too, with good diversity and abundance,” Murgatroyd said.

“That was surprising to me because Djibouti is so dry, and at first glimpse it doesn’t look like it’s going to give up much. So I was super excited,” she told GroundUp.