The boss of Britain’s biggest drugmaker, Pascal Soriot, has warned that the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss are damaging the planet and human health, as it announced a $400m (£310m) plan to plant 200m trees by 2030.

The offsetting scheme is one of the biggest tree-planting programmes globally. In 2020, AstraZeneca pledged to plant and maintain more than 50m trees by the end of 2025, with 10.5m trees of 300 different species planted so far across Australia (in collaboration with Aboriginal people), Indonesia, Ghana, the UK, the US and France.

On Wednesday, the company expanded that programme with a $400m investment in reforestation and a commitment to plant more than 200m trees by 2030 and ensure their long-term survival. The trees will be planted in Brazil, Vietnam, Ghana, Rwanda and India. Countries with tropical forests such as Brazil and Indonesia absorb the most carbon dioxide, and are critical in the battle against global heating.

Deforestation worsened last year when an area the size of Switzerland was cleared from the most pristine rainforests, despite a political pledge made by world leaders at the Cop26 summit in 2021 to halt their destruction. The tropics lost 10% more forests than in 2021, according to figures from the World Resources Institute and the University of Maryland. The forest loss produced 2.7 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide emissions, equivalent to India’s annual fossil fuel emissions.

AstraZeneca says its tree-planting programme will remove an estimated 30m tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. It will offset some of the carbon emissions of the contractors it uses in its supply chain, as the drugmaker aims to become net zero by 2045. The carbon credits are shared with the governments of the countries where the trees are planted “to avoid double counting”, Soriot said.

Carbon-offsetting schemes are increasingly under scrutiny as many projects appear to have no positive impact on the climate, with scientists calling for the unregulated system to be reformed urgently. Regulators are increasingly banning firms from making offsetting-based environmental claims unless they can show that they work.

“The twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss are damaging the planet and harming human health,” Soriot said.

Speaking to the Guardian ahead of an event chaired by former Bank of England governor Mark Carney during London Climate Week, he said AstraZeneca’s projects would create jobs for local people and support up to 80,000 livelihoods. It is partnering with NGOs and the projects will be audited and assessed by independent experts, including the European Forest Institute, the firm said.

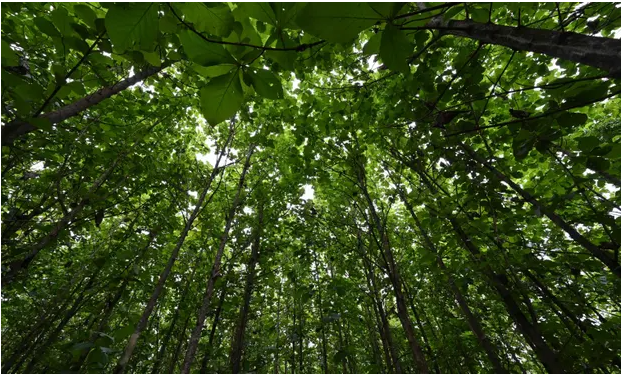

As experts stress that the right species of trees need to be planted in the right locations and monitored over years to come, Soriot said AstraZeneca’s programme was not about planting “the same trees … in big lines”.

“We also want to restore biodiversity,” he said. “So that’s why we have 300 species of trees and plants. We want to make sure that we restore the forest the way it was before. That is different by country. In fact, in Australia, for instance, it even varies by region.”

The drugmaker plans to use drones to assess tree growth and health, and hi-res satellite imagery to monitor the condition of trees and the projects’ impact on water and soil and carbon stocks.

While tree-planting projects can be successful at removing carbon from the atmosphere, many schemes do not monitor whether or not trees survive. In 2021, a global review of tree-planting initiatives in the tropics and subtropics since 1961 found that while dozens of organisations reported planting a total of 1.4bn trees, just 18% mentioned monitoring and only 5% measured survival rates.

Many experts argue that natural regeneration is nearly always better, where trees grow from seeds that fall and germinate in situ, although it is slower. The Woodland Trust, a charity in England and Wales, says naturally regenerated trees often survive better than planted trees.

Natural restoration of forests that involves no tree planting can absorb as much as 40 times the amount of carbon than plantations, according to research, although businesses are unlikely to be able to claim these schemes as offsets.

Soriot said: “Whilst some of our projects will make use of natural regeneration in places, the areas we are working in are often so degraded that it would take decades for trees to naturally recolonise, if they ever manage to.”