In the lobby of Fresno airport is a forest of plastic trees. A bit on the nose, I think: this is central California, home of the grand Sequoia national park. But you can’t put a 3,000-year-old redwood in a planter (not to mention the ceiling clearance issue), so the tourist board has deemed it fit to build these towering, convincing copies. I pull out my phone and take a picture, amused and somewhat appalled. What will live longer, I wonder: the real trees or the fakes?

I haven’t come to Fresno to see the trees; I’ve come about the device on which I took the picture. In a warehouse in the south of the city, green trucks are unloading pallets of old electronics through the doors of Electronics Recyclers International (ERI), the largest electronics recycling company in the US.

Waste electrical and electronic equipment (better known by its unfortunate acronym, Weee) is the fastest-growing waste stream in the world. Electronic waste amounted to 53.6m tonnes in 2019, a figure growing at about 2% a year. Consider: in 2021, tech companies sold an estimated 1.43bn smartphones, 341m computers, 210m TVs and 548m pairs of headphones. And that’s ignoring the millions of consoles, sex toys, electric scooters and other battery-powered devices we buy every year. Most are not disposed of but live on in perpetuity, tucked away, forgotten, like the old iPhones and headphones in my kitchen drawer, kept “just in case”. As the head of MusicMagpie, a UK secondhand retail and refurbishing service, tells me: “Our biggest competitor is apathy.”

Globally, only 17.4% of electronic waste is recycled. Between 7% and 20% is exported, 8% thrown into landfills and incinerators in the global north, and the rest is unaccounted for. Yet Weee is, by weight, among the most precious waste there is. One piece of electronic equipment can contain 60 elements, from copper and aluminium to rarer metals such as cobalt and tantalum, used in everything from motherboards to gyroscopic sensors. A typical iPhone, for example, contains 0.018g of gold, 0.34g of silver, 0.015g of palladium and a tiny fraction of platinum. Multiply by the sheer quantity of devices and the impact is vast: a single recycler in China, GEM, produces more cobalt than the country’s mines each year. The materials in our e-waste – including up to 7% of the world’s gold reserves – are worth £50.9bn a year.

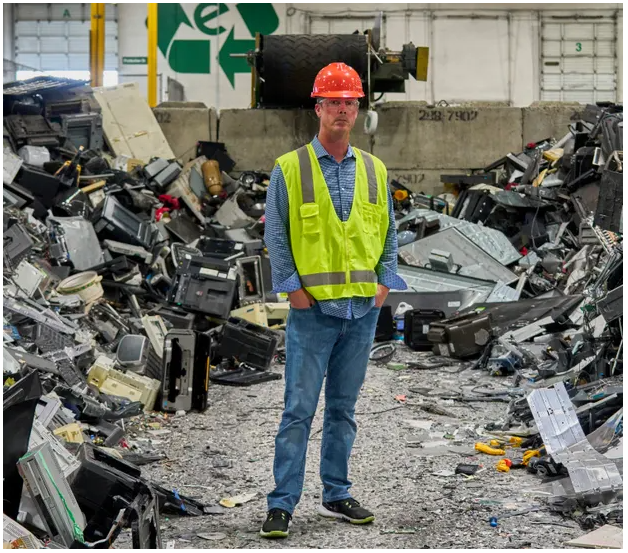

Aaron Blum, co-founder and chief operating officer of ERI, arrives wearing the corporate uniform of a tech executive: navy hoodie and jeans. “You’ll need these,” he says, handing me a pair of bright orange earplugs. Blum and a friend started ERI back in 2002, after leaving college. California had just banned electronics from landfills due to hazardous chemical contents – but little recycling infrastructure existed. “I didn’t know anything about electronics. I was a business major,” Blum says. Today, ERI has eight facilities across the US and processes 57,000 tonnes of scrap electronics a year.

To get to the factory floor, we pass through a scanner. Security is tight for a reason: millions of dollars’ worth of still-functioning or repairable electronics passing through make it a tempting target for thieves. In the loading bay, a goateed guy named Julio is unloading pallets of shrink-wrapped monitors from a Salvation Army truck – charity shops are a major source of ERI’s product. Everything that arrives is scanned before being dismantled and sorted. “You can’t shred certain materials, so you’ve got to do a sort,” Blum says.

Electronics are piled everywhere: flatscreens, DVD players, desktops, printers, keyboards. At a set of tables, nine men are taking apart large TVs, their electric screwdrivers emitting a low whiz. Another is smashing a monitor from its casing with a hammer (“Due to the adhesive”). The dismantling crews, Blum says, will handle up to 2,948kg (6,500lb) of devices a day.

We pass a noticeboard marked Focus Material, on which actual parts have been pinned as visual aids: motherboards, wire scraps, monitor casings. “This hits home more than reading a document,” Blum says.

Scrap recycling contains so many different materials that the industry has developed its own shorthand: light copper is “Dream”, No 1 copper wire is “Barley”, insulated aluminium wire is “Twang”. There’s no such poetry here, however. Instead, the extracted pieces are thrown into boxes scrawled with things like Copper and CAT-5 wiring. Inside one I notice a coil of LED Christmas lights. “During the holidays we get a ton of these. This is all copper, in the wire,” Blum says, grabbing a handful. “We have to go through and manually cut the bulbs off.”

Paranoid about losing industrial secrets to China, companies would rather have their old machines wiped and shredded

Some materials – paper, batteries – must be removed for safety reasons. “If something gets through that can’t be shredded, you can have a fire or an explosion,” Blum says. “When you’re shredding metal, it gets really hot.” Heat-sensing cameras constantly scan the factory floor for hot pockets, and the workers wear masks and gloves: e-waste contains toxicants ranging from lead and mercury to polybrominated flame-retardants and PFAS.

The centrepiece of the facility is the shredder, a hulking beast that stretches the length of the building, three storeys high, making a prodigious racket. (Hence the earplugs.) Once the waste has been sorted, a worker in a Bobcat telehandler carries it over to the conveyor’s gaping maw, where ultra-hardened spinning blades cut through aluminium and plastic like ice in a blender. “When you’re shredding electronics, you’re creating dust that contains lead from the circuit boards, so we have collection hoods sucking up all the dust,” Blum hollers. The dust has to be disposed of as hazardous waste. I nod, exhilarated by the sheer violence of it.

Magnetic belts, air-sorters and filters separate the materials as they pass along the shredder, dropping them into giant “super sacks”. We stop at one and look down at a treasure haul of silver-grey flecks. “We call this precious metal fines,” Blum says. “It’s gold, silver and palladium from the circuit boards.” A single sack’s contents are probably worth enough to buy a decent car.

Near the end of the line, more metals roll into their super sacks. ERI’s biggest material streams, by weight, are steel, plastic, aluminium and brass. The circuit boards are sent to LS Nikko, a metals manufacturing giant based in South Korea; the aluminium goes to the US smelting giant Alcoa. “The steel might go to your large steel buyers in the US – they might send it to mills in Turkey, but otherwise, everything stays domestic.”

ERI charges customers a fee for disposal, dismantling, data removal and recycling. Most are motivated not by reducing waste, Blum says, but by cybersecurity: “Ninety-nine per cent of the electronics you have today have your data on them. So data has become very, very important.” Paranoid about losing industrial secrets to China, companies would rather have their old machines wiped and shredded. “We have Homeland Security come to our facilities. They will escort the material to the shredder, stand watching while we run the material through, and sometimes even take the shred out.”

As we pass back through the factory, something catches my eye: a pallet of TV screens from a major manufacturer, still neatly boxed and plastic-wrapped. They are brand new, but here to be shredded: “They don’t want this product resold and competing against their new products, so they want it all destroyed.”

I’d expected to see this at ERI, but not so brazenly. Manufacturers and retailers routinely destroy returns and unsold items, known as deadstock, en masse. As Kyle Wiens, founder of the repair chain iFixit, tells me, these “must-shred” contracts are the “dirty secret” of the recycling industry. (“The recyclers are desperate for manufacturer contracts, so they’ll do anything and keep their mouths shut,” Wiens says.) In 2021, for instance, an ITV News investigation in the UK found Amazon was sending millions of new and returned items a year to be destroyed. (Amazon says it has since stopped the practice.)

In 2020, Apple sued a Canadian recycler for reselling some of the 500,000 devices it had sent for shredding. The recycler, GEEP, blamed rogue employees – but the implication that the devices had been working well enough to sell set off a wider scandal. The unfortunate truth is that companies destroy new and nearly new products all the time. Luxury and technology brands are reluctant to discount or donate unsold items that might undermine sales of new models. Burberry, for one, admitted to incinerating £105m of unsold items in the five years to 2018, to stop them being sold at discounted rates (Burberry also says it has ended the practice). In other cases, the financial upside of processing unsold items or returns is not worth the costs, so it’s cheaper to write it off. Burn it or bury it, wasting is cheap.

There’s an old axiom that they don’t make things like they used to. Goods cheaply bought are cheaply made – no surprise there. But when it comes to e-waste, a more serious allegation is “planned obsolescence”, by which industries design products with artificially short lives, so they need to be replaced more quickly.

Some obsolescence is good: replacing cars for models with more fuel-efficient engines, for example. Similarly, we know the rapid churn of smart devices in the last decade has been driven not by faulty products, but by the relentless pace of technological progress.

Even so, the electronics industry has faced allegations that planned obsolescence is contributing to our rising tide of e-waste. In 2017, for example, Apple admitted it had been using software to slow older iPhones. After multiple lawsuits, including a $500m civil action it settled in 2020, the company eventually apologised. But it has also engaged in a pattern of behaviour critics allege undermines its self-image as a sustainable business: the iPhone 13, introduced in 2021, initially included a feature that would disable the Face ID unlock system if the screen was replaced with one not made by Apple.

Most of us would have no idea how to fix our phone and even if we did, many manufacturers have removed the ability for consumers even to replace batteries, arguing that repairs must be done by professionals or even by the company itself – for a hefty fee, of course. iPhone owners in the US who want to repair their phone, for example, must pay a $1,200 deposit to hire Apple’s special tools. I find this disheartening, because as a teenager in the mid-2000s I spent my weekends working at a mobile phone repair stall in the local shopping centre, happily swapping out dud batteries and broken screens from old Nokias and Motorolas for new ones.